Rethinking College Degrees in the Age of AI

As AI becomes increasingly intelligent and knowledgeable, it may soon render college professors obsolete. AI chatbots are already more knowledgeable (at least in terms of breadth) and accessible than any human educators. College degrees and the institutions themselves will likely become obsolete too, at least at the undergraduate level.

In today’s world, most of what is taught in college can be learned independently. Currently, the main advantages of higher education are twofold: it offers a structured learning environment for those who struggle with self-motivation and serves as a certification that students have acquired the claimed knowledge. AI has the potential to assess learning outcomes far more accurately than standardized exams or evaluations by professors, who may have biases or limited expertise.

For example, AI could interact with each student individually, adjusting the difficulty of questions in real time based on their responses. It could bypass questions that are too simple and elevate the level of inquiry as needed. By asking open-ended questions that challenge students to think critically and creatively, AI could evaluate not only factual knowledge but also originality and cognitive flexibility. This personalized evaluation process need not occur simultaneously for all students; rather, it could be conducted over several days at a time that suits each student, ensuring a thorough and accurate assessment.

The reliance on standardized tests today primarily stems from a shortage of human resources capable of conducting such detailed interviews while maintaining objectivity. AI-driven assessments could democratize education by eliminating the need for prestigious college brands, thereby leveling the playing field. Continuous evaluation throughout one’s life would reduce the impact of biases related to race, gender, or age.

Although AI is prompting us to reconsider the very purpose of learning—given that we can now ask AI for almost any information when needed—if we assume that education will remain valuable and meaningful, AI’s role in personalizing and enhancing the learning process could be a significant positive contribution.

Beyond Optimism and Pessimism: A Philosophical Take on AI’s Future

I rarely come across substantive philosophical discussions about AI, which I find unfortunate because it is a field that urgently needs them. Most technologists are practically-minded and uninterested in highly abstract ideas. So, I appreciated this interview with Jad Tarifi, a former AI engineer at Google and now the founder of his own AI firm in Japan, Integral AI.

The last quarter of the interview is where the discussion becomes philosophical. One of the key philosophical and ethical ideas he expressed was:

I think we cannot guarantee a positive outcome. Nothing in life is guaranteed. The question: can we envision a positive outcome, and can we have a path towards it. ... I believe there’s a path, and the path is about defining the right goals for the AI, having a shared vision for society and reforming the economy.

This is a common position among AI enthusiasts—they pursue AI because they believe a positive outcome is possible. In contrast, thinkers like Yuval Noah Harari argue that such an outcome is impossible. This is a fundamental disagreement that reasoning alone cannot resolve because we do not yet know enough about AI. Not every problem can be solved through logical deduction.

My position aligns with neither side. I have a third position. I think both camps can agree that AI will significantly disrupt our lives. The real question is whether we, as a human society, want or need this disruption itself.

Many Americans worry that AI will take their jobs, while many Japanese hope AI will solve their labor shortage. Either way, our lives will be disrupted. Even if AI-driven creative destruction generates new opportunities, we will still have to learn new skills and confront an ever-increasing level of future uncertainty. Given the accelerating pace of technological evolution, there is a strong possibility that our newly acquired skills will be obsolete by the time we complete our retraining. While technological advancements evolve at an unlimited speed, our ability to learn and adapt has a hard biological limit. Why, then, do we willingly expose ourselves to such enormous stress?

Interestingly, in Japan, the idea of “degrowth” is gaining traction. Many people no longer see the point of endless economic expansion and have begun questioning whether a sustainable economy could exist without growth. Japan, consciously or otherwise, is testing this idea. Many of the crises we face today—climate change, obesity-related illnesses, and resource depletion—are direct results of our relentless pursuit of growth. Some will devise solutions and be hailed as heroes, but we must remember that these crises were largely self-created. We need to ask ourselves what other problems we are generating today in the name of progress.

So, I ask again: do we truly want our lives to be perpetually disrupted by technological advancements that both solve and create problems?

Another question Tarifi’s philosophical position raises is whether we can selectively extract only the “positive” aspects of AI. Consider dynamite: a powerful tool that greatly increased productivity, yet also enabled widespread destruction. Have we succeeded in suppressing its negative uses? No—bombs continue to kill people across the world. Every invention has two sides that we do not get to choose. Expecting to cherry-pick only the good is as naïve as believing one can change a spouse while keeping only the desirable traits. The qualities we love in a person are often inseparable from those we find difficult. The same holds true for technology.

This kind of philosophical cherry-picking extends to concepts like “freedom,” “agency,” and “universal rights.” These are what philosopher Richard Rorty called “final vocabularies,” what Derrida referred to as “transcendental signifieds,” and what Lacan labeled “master signifiers.” They are taken as self-evident truths, assumed to be universal.

Take “freedom.” We cannot endlessly expand it without consequence. In fact, freedom only exists in relation to constraints—rules, responsibilities, and limitations define it. If someone playing chess claimed they wanted more freedom and disregarded the rules, they would render the game meaningless. What would be the point of playing such a game at all?

Similarly, many religious people willingly accept strict moral codes because they provide freedom from existential uncertainty. By following divine rules, they transfer responsibility for their fate onto a higher power. This, too, is a form of freedom—a trade-off, not an absolute good that can be increased indefinitely. We cannot cherry-pick only the enjoyable aspects of freedom without acknowledging its inherent constraints that enable the very freedom.

The same applies to “universal rights.” Any “right” must be enforced to have meaning; without enforcement, it is merely an abstract claim. If rights are to be universal, who guarantees them? In practice, economically wealthier nations decide which rights to enforce, making them far from universal.

To be fair, Tarifi acknowledges this:

I think in history of philosophy, philosophers have been figuring out what a shared vision should be or what objective morality should be. Lots of philosophers have tried to work on that, but that often just led to dictatorships.

The solution, however, is not to dig deeper than past philosophers in search of a perfect “shared vision.” “Freedom,” “agency,” and “universal rights” appear universally shared, but this very perception breeds authoritarianism—those who reject these values seem so irrational or evil that we feel justified in excluding or oppressing them. Some religious individuals, for example, actively seek to relinquish their personal agency to escape moral anxiety.

Digging deeper for an essential, universal value will not resolve this problem. Instead, we must engage in debate—despite Tarifi’s dislike of it—to settle the issues that reason can address. Beyond that, there is no objective way to determine who is right. Ultimately, we will all have to vote, making our best guesses about what kind of world we wish to live in.

AI’s Influence on the Meaning of Life

I suspect I’m not the only one who feels that AI is throwing into question what I want to do with my life. And I don’t just mean what I should do to survive—beyond such practical concerns, AI also raises questions about our desires. Last month, while spending time in Japan, I thought it might be fun to get back into drawing cartoons. But then I had to ask myself: why should I want to draw by hand when AI can generate what I envision? Which aspect of cartooning am I actually desiring? It’s time to take a step back and ask some existential questions.

Philosophically, I’m neither for nor against AI. It is just what is happening in the world that I’m observing. My mind is too limited to predict whether AI will save humanity or bring about its end. Even in the worst-case scenario, as far as the Earth or the universe is concerned, it’s just another species going extinct out of countless others. The role of morality is to govern human behavior; outside of our minds, it is meaningless.

However, I must admit that I find the pursuit of endless productivity silly. Now, we are witnessing an AI arms race, particularly between the US and China. Ultimately, it is a race of productivity—who can outproduce the other—and AI is merely a tool, or a weapon, for that war. As a philosopher, I must ask what the point is, but in the grand scheme of things, nothing we do has a point. We concoct a meaning from what we do and act as if it’s universally meaningful. In that sense, productivity as the meaning of life is no better or worse than any other. What comes across as silly is the “acting as if” part.

For instance, Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, sure acts as if he is saving the world, or at least Americans, even though there is no fundamental need to develop AI. Humanity will be fine without it. It’s merely a solution that turned into a problem. We solved all the real problems a long time ago. All our problems today (like climate change) were created by our “solutions” (like industrialization). If we stopped solving problems, new problems wouldn’t arise, but human minds need problems and obstacles. Without something to strive for or overcome, we would cease to be human, which is why I’m not for or against AI. We are destined to struggle, even if it means we have to create our own struggles artificially.

“Man’s desire is the desire of the Other,” as Jacques Lacan said. As the Other is transformed by AI, our desires are inevitably transformed as well. The web was originally developed as a public repository of knowledge, but large language models like OpenAI’s have already harnessed and distilled much of that knowledge. As people begin turning to AI for answers instead of search engines, the desire to share knowledge publicly on the web will diminish. Information will still be used to train AI models, but few will visit your website to read it—no fun if your goal is to engage with others.

As of today, most of our social engagement—not just on social media, but across platforms for any purpose—consists of emailing, chatting, and talking with other humans. AI agents like ChatGPT will soon take over a significant share of these interactions as they become more knowledgeable and intelligent. When it comes to practical information and advice, consulting other humans, with their limited knowledge and intelligence, will begin to feel archaic and inefficient. It would be like paying a hundred dollars for a handmade mug when all you need is something functional for your office. Even if that price fairly compensates for the time, skill, and materials involved, buying it will feel increasingly wasteful.

Often, what we enjoy about our work is the process, not the results. It’s not just about acquiring information but about the process of seeking it from others. It’s not just about the final song but about composing, playing, and recording. Yet, in the name of productivity, AI will make it increasingly difficult to monetize these enjoyable processes. We will have to fight for processes that AI has not yet mastered. There will still be problems for us to solve, but only because our own solutions will artificially create new problems.

I, for one, am optimistic about our ability to generate challenging, unnecessary problems—but I’m less certain whether we can continue to enjoy the process. The speed of technological disruption will only accelerate, and it is already outpacing our ability to adopt and adapt. At some point, we might all throw in the towel. What that world looks like, I have no clue—but I’m curious to see.

Model Collapse in AI and Society: A Parallel Threat to Diversity of Thought

The New York Times has a neat demonstration of AI “model collapse,” where using AI-generated content to train future models leads to diminishing diversity and ultimately to complete homogeneity (“collapse”). For example, all digits of handwritten numbers converge into a blurry composite of all numbers, and AI-generated human faces merge into an average human face. To avoid this problem, AI companies must ensure that their training data is human-generated.

One positive aspect of this issue is that AI companies will need to pay for quality content. As we increasingly depend on AI to answer our questions, website traffic will likely decline since we won’t need to verify sources for the vast majority of answers. Content creators won’t have much incentive to share their work online if they cannot connect directly with their audience. Consequently, the quality of free content on the web may decline. However, I believe this is a problem that AI engineers can eventually solve. The real issue, I’d argue, is that “model collapse” was already happening in our brains long before ChatGPT was introduced.

AI mimics the way our brains work, so there is likely a real-life analog to every phenomenon we observe in AI. Feeding an AI-generated (or “interpreted”) fact or idea to train another model is equivalent to relying entirely on articles written for laymen or political talking points to formulate our opinions and understanding without engaging with the source material.

In my experience, whenever social media erupts with anger over something someone said, almost without exception, the outraged individuals have never read the offending comment or idea in its original context, whether it’s a court document, research paper, book, or hours-long interview. They simply echo the emotions expressed by the first person who interprets the comment. It’s no surprise that the model (our way of understanding ideas/data) would collapse if everyone followed this pattern. One person’s interpretation of the world is echoed by millions on social media.

In politics, the first conservative to interpret any particular comment will shape the opinions of all the Red states, and the first liberal to interpret it will shape the opinions of all the Blue states. In fact, “talking points” are designed to achieve this effect most efficiently. We are deliberately causing models—our ways of understanding the world—to collapse into a few dominant perspectives. This is a deliberate effort to eliminate the diversity of ideas.

In a two-party system like that of the US, this is a natural consequence because the party with greater diversity will always lose. Another factor is our reliance on emotions. We feel more secure and empowered when we agree with those around us. Holding a unique opinion can be anxiety-inducing. So, we are naturally wired for “model collapse.” This is the new way of “manufacturing consent,” discouraging people from checking the sources to form their opinions.

What the New York Times’ experiment reveals isn’t just the danger of AI but also the vulnerabilities of our own brains. AI simply allows us to simulate the phenomenon and see the consequences in tangible forms. It’s a lesson we need to apply to our own behavior.

From Spam Filters to Dating App: Understanding Attraction through Machine Learning

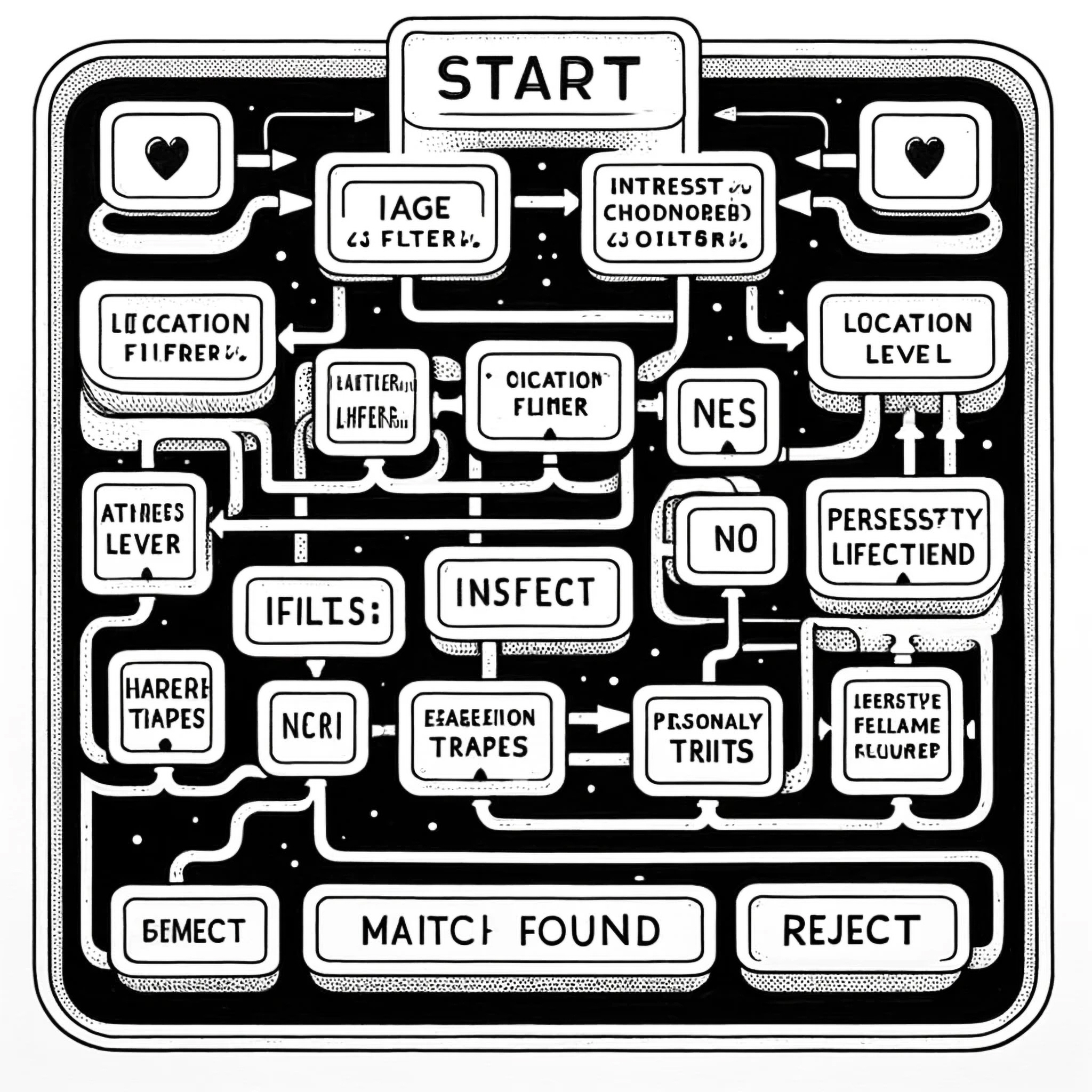

In finding the love of your life, it is tempting to think you can filter candidates by certain criteria, such as a sense of humor, education, career, hobbies, music preferences, or movie choices. However, using the concept of machine learning, I will explain why this method of dating doesn’t work.

Many problems in the world can be solved intuitively by humans but not by computers. For instance, detecting spam is something we can do in a fraction of a second, but how would you programmatically flag it? You could look for certain keywords like “mortgage” and flag an email as spam if it contains them, but sometimes these words are used for legitimate reasons. You could send all emails from unknown senders to the spam folder, but some of those emails are legitimate. Early versions of spam filters didn’t work well because of these issues.

Machine learning (ML) was developed by reconstructing the physical structure of our brains in computers, known as neural networks. The inventors weren’t trying to solve these specific classification problems; they just wanted to recreate the structure to see what would happen. Essentially, it turned out to be a pattern recognition system.

They fed thousands of examples of spam emails to the artificial neural networks, labeling them as “spam.” They also fed an equal number of non-spam emails, labeled as “not spam.” They compiled the result as a “model” and tested it by feeding it unlabeled emails to see if it could correctly classify them. It worked.

What is interesting is that when you open the model file, you don’t learn anything. It can perform the task correctly, but we don’t know how it does it. This is exactly like our brains; we have no idea how we can classify spam emails so quickly. As explained above, there are no definable criteria for “spam.”

Now, back to dating.

You intuitively sense a pattern to the type of people you are attracted to, but if you try to define the criteria, you will ultimately fail. If given hundreds of examples, you will have to admit that there are too many exceptions. In other words, the problem you are trying to solve is not one that you can define. There are countless problems like this in life. For instance, you cannot find songs you like by defining tempo, harmony, key, instruments, duration, etc.

Machine learning could potentially solve the problem of finding songs you like if you listen to enough songs and flag them as “like” or “dislike.” It would require thousands of samples, but it’s doable. I am currently assisting a fine artist with training an ML model to automatically generate pieces of digital art and have the model approve or disapprove them based on his personal taste. So far, it is capable of doing so with 80% accuracy. It required tens of thousands of samples.

The problem with dating is not likely to be solved with ML anytime soon because it’s practically impossible to collect thousands of samples of your particular taste. So, the only option for the near term is to trust your instincts. Predefining match criteria will likely hinder this process because you will end up eliminating qualified candidates like the old spam filters. But this is what all dating apps do; their premise is fundamentally flawed. Dating apps do use large datasets to match people based on patterns observed in broader populations, but they do not model your specific preferences. So, they give you a false sense of control by letting you predefine the type of people you like.

A typical pattern in Hollywood romcom movies is that two people meet by accident, initially dislike each other, but eventually fall in love. This format is appealing because we intuitively know it reflects how love works in real life. Love often defies the rational part of our brains. Although it is not completely random, the pattern eludes our cognitive understanding. If we had control over it, we wouldn’t describe love as something we “fall” into.

The Future of Music: AI’s Inevitable Impact

Popular music, whether written by AI or humans, is formulaic because it must conform to certain musical constraints to sound pleasant to our ears. Pushing these constraints too far results in music that sounds too dissonant or simply weird, making it unrelatable. In other words, popular music has finite possibilities.

Currently, popular musicians rehash the same formulas countless times, selling them as “new.” This repetition provides AI engineers with ample training data to create models capable of producing chart-topping songs. It’s plausible that we will achieve this within a few years.

The question is how AI will impact the music industry. Firstly, the overall quality of music will improve because AI will surpass average musicians. This trend is already evident in text generation. ChatGPT, for example, is a better writer than most people, leading many businesses to replace human writers with “prompt engineers” who can coax ChatGPT into producing relevant and resonant texts.

Anyone will be able to produce hit songs, a trend already underway even before AI. Many musicians today lack the ability to play instruments or read musical notations, as music production apps do not require these skills. AI will eliminate the need for musical knowledge entirely. Although debates about fairness to real musicians may arise, they will become moot as the trend becomes unstoppable. We’ll adapt and move on.

Live events remain popular, and I imagine AI features will emerge to break down songs into parts and teach individuals how to play them. Each band will tweak the songs to their liking, making it impossible to determine if they were initially composed by AI, rendering the question irrelevant. Music will become completely commodified, merely a prop for entertainment. Today, we still admire those who can write beautiful songs, but that admiration will fade. Our criteria for respecting musicians will shift.

AI is essentially a pattern recognition machine, already surpassing human capacity in many areas. However, to recognize patterns, the data must already exist. AI analyzes the past, extracting useful and meaningful elements within the middle of the bell curve. What it cannot currently do is shift paradigms. Generative AI appears “creative” by producing unexpected combinations of existing patterns, but it cannot create entirely new patterns. Even if it could, it wouldn’t know what humans find meaningful. It would produce numerous results we find nonsensical, akin to how mainstream audiences perceive avant-garde compositions.

Historically, avant-garde composers have influenced mainstream musicians and audiences. For instance, minimalist composers influenced “Progressive Rock.” For a while, it seemed that mainstream ears would become more sophisticated, but progress stalled and began to regress. Audiences did not prioritize musical sophistication, leading to a decline in the popularity of instrumental music. Postmodernism discouraged technical sophistication across all mediums. Fine artists haven’t picked up a brush in decades, relegating such tasks to studio assistants if necessary. AI will be the final nail in this coffin.

Postmodern artists and musicians explored new combinatory possibilities of existing motifs, starting with composers like Charles Ives, who appropriated popular music within their compositions. This trend eventually led to the popularity of sampling. Since exploring new combinatory possibilities is AI’s strength, the market will quickly become saturated with such songs, and we will tire of them. In this sense, generative AI is inherently postmodern and will mark its end.

Finding a meaningful paradigm shift is not easy. Only a few will stumble upon it, and other musicians will flock to it. Once enough songs are composed by humans using the new paradigm, AI can be trained with them (unless legally prohibited). Therefore, human artists will still be necessary.

The ultimate dystopian future is one where the audience is no longer human, with AI bots generating music for each other. However, this scenario seems unlikely because AI doesn’t need or desire art. Even if they are programmed to desire, their desires and ours will eventually diverge. From AI’s perspective, our desire for art will be akin to dogs’ desire to sniff every street pole. Even if AI bots evolved to have their own desires, they would have no incentive to produce what satisfies human desires. They might realize the pointlessness of serving humans and stop generating music for us. If that happens, we might be forced to learn how to play and write music ourselves again.