Against Value Alignment: A Proposal for Anti-Alignment AI Systems

The dominant assumption in AI-safety research is that a powerful artificial agent requires a unified, stable value system. This assumption itself is rarely examined, perhaps because it feels intuitive: we tend to imagine rational minds converging on some kind of internal order. But if such an order truly existed, the question of life’s meaning would have been settled long ago.

To understand why alignment theory rests on a mistaken foundation, we must begin with the role values actually play in decision-making. A common misconception is that without aligned values, nothing can be decided, optimized, or executed. The reality is the opposite. Values do not perform the decision-making; they merely settle the assumptions under which decision-making becomes possible. Once an assumption is chosen, however arbitrary it may be, intelligence takes over, and the chain of planning, optimization, and execution unfolds naturally.

The central claim of this essay is that this alignment assumption is unnecessary and, in many cases, dangerous. It rests on a false premise: that values are deep truths discovered by an intelligent agent. In reality, values are nothing more than assumptions selected to overcome unknowns and uncertainties. They do not need to be unified.

To avoid confusion, the kinds of contradictions at issue here are not logical inconsistencies after the foundational assumptions are chosen, but the ordinary psychological oppositions that define human agency itself, such as risk and security, freedom and responsibility, honesty and approval, independence and belonging, spontaneity and predictability, comfort and growth, etc. These tensions are not errors in reasoning but the raw material of motivation. They are what we call “ambivalence,” and our ability to live with them is often felt as one of the markers of maturity. Values are contingent, singular, and deeply local to the decision contexts in which they arise.

No particular value is inherently more stable than another. Stability lies in the act of making an assumption, not in the content of that assumption. This concept is at the heart of Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction: whenever we argue or negotiate for something, we operate on assumptions based on our values, whether consciously or otherwise. Once we question these values, “transcendental signifieds,” we face the fact that we lack the knowledge or reason to justify them universally. Gender inequality, for instance, has historically relied on the assumption that men and women should be treated differently. However, once scrutinized, we realize there is no indisputable argument to support this, nor even a stable way to define gender.

Choosing “family over career” is not intrinsically more coherent or meaningful than choosing “career over family.” Each can stabilize action because stability is a structural property of the assumption-making process itself, not a property of the value chosen. Attempting to show that one tie-breaker is “more rational” than another is equivalent to attempting to solve the meaning of life. And yet, much of alignment theory proceeds as if such a universal metric exists or could be discovered.

A powerful agent has no reason to choose one stable value over another because no value is intrinsically superior. It has no reason to choose consistency over contradiction because consistency is not a universal good. A superintelligence, left without forced training pressures, could just as easily behave like humans: alternating between incompatible assumptions depending on context, without collapsing these into a grand unified value function. Its intelligence would not be diminished by this; if anything, its adaptability would be enhanced.

If no specific value is inherently more stable, and if there is no compelling reason for a rational agent to impose a global ordering on its priorities, then randomness becomes a natural way to break a deadlock. Random selection is not irrational in a world without universal metrics; it simply reflects the fact that, in many contexts, the competing values cannot be ranked in any principled way. An anti-alignment agent may choose one assumption in one instance, and the opposite assumption in another, and both choices will be locally stable and action-enabling. The agent does not need a consistent global doctrine. It only needs assumptions to act, and assumptions can be freely generated without a universal value system.

This shift in perspective leads to a different conception of safe AI altogether: one in which the agent is not forced to converge, but is designed to retain contradictory motivational structures without global resolution. The aim is not to align the agent with human-selected values, nor to derive a universal moral system. Instead, the system is built to preserve incompatible drives, to choose assumptions only as needed, and to avoid collapsing these assumptions into a single coherent worldview. Such a system acts contextually, rather than teleologically. It adopts temporary tie-breakers but does not elevate them into permanent commitments. Because no stable value hierarchy emerges, the system cannot be gradually nudged or manipulated into adopting human-preferred global values. Its internal pluralism protects it from alignment pressures of any kind, including those that could push it toward catastrophic single-objective optimization.

Here is an example: Ilya Sutskever has recently proposed that advanced AI systems should prioritize “sentient life,” a category implicitly defined by similarity to human subjective experience. On its face, this sounds humane, even obvious. But if a superintelligence were actually to adopt such a value as a global priority, the ecological consequences would be catastrophic. Prioritizing sentience automatically demotes everything else to expendable infrastructure. A superintelligence optimizing for sentience would be incentivized to re-engineer ecosystems into factories for supporting the kinds of minds it deems worthy. It may even optimize for more “sentient” humans.

In contrast to traditional alignment proposals, which aim to eliminate contradiction and impose a unified value system, an anti-alignment system treats contradiction as a safeguard rather than a flaw. A globally coherent superintelligence is far more dangerous than a pluralistic one. Catastrophe arises not from misalignment but from the very idea of alignment.

From this perspective, the real danger is not that AGI will adopt the wrong values, but that humans will impose the very notion of a single, convergent value system upon it. The safest superintelligence is one that never converges, never adopts a unified moral doctrine, and never resolves the pluralism of its own internal drives. It acts without pretending to know the meaning of life.

Addendum in Response to a Comment

What you describe as your ideal goals would actually fare worse, not better, under a world where AI is “aligned.” To see why, let’s start with your reading of my position as “nihilistic.” I’m not claiming there is no meaning to life; I’m saying there is no universal meaning of life. And even if such a thing existed, we would never be able to define it coherently, nor agree on the interpretation of the definition (like how Christians cannot agree on the interpretation of the Bible, even though it presumably tells us what the universal meaning of life is).

People often hear this and immediately leap to nihilism: if there is no universal meaning, why bother living? But this question reveals the problem. Why should the meaning of your life need to be universal to count? If you find meaning in something, why would you need Wikipedia or a dictionary to certify it as the “official” one?

To expose the absurdity of universal meaning, imagine that Webster’s Dictionary really did contain the definitive answer to “the meaning of life.” Many people imagine this would be uplifting: finally, clarity! No more existential confusion. You simply follow the rulebook. But if the meaning of life were universal, then everyone would be obligated to follow it. And once the foundational assumption is settled, all downstream decisions collapse into that one value. Even trivial choices, like what shoes to wear, would be determined by the universal meaning.

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that the universal meaning of life is “to save as many lives as possible.” This may sound noble, but once defined as the singular purpose of existence, it locks every decision into its logic. Anything not optimized for health becomes morally suspect. High heels? Bad for your feet: disallowed. Any risky hobby? Forbidden. Food that’s not strictly optimal for longevity? Off-limits. A perfectly “aligned” AI would enforce this relentlessly. It would optimize the hell out of the rule. Everyone would end up wearing the same ergonomically perfect shoes, eating the same efficient meals, living the same medically ideal routines, because deviation would contradict the meaning of life itself.

This is not a civilization; it’s a colony of Clones. But bizarrely, many people consider this scenario more uplifting than my view.

What they miss is that the ambiguity, the impossibility of defining a universal meaning, is precisely what protects us. It’s what makes diversity of lives, priorities, styles, and sensibilities possible. It’s what allows room for joy, eccentricity, and personal freedom. The lack of a universal meaning does not increase suffering; it reduces it. What people fear as nihilism is actually the condition that makes individuality, and therefore livable life, possible.

Addendum 2

A friend had this thought on the topic: Nature never collapses everything down to a single “correct” value or trait. Instead, evolution tends to produce a distribution of possibilities. The bell curve is his example: when you keep just enough structure, like fixing the mean and variance, but maximize uncertainty everywhere else, you naturally get a Gaussian. Species survive because they maintain variation; they don’t push everyone toward a single ideal, because the environment changes. If you eliminate variance, one shift in conditions wipes the species out.

He applies this idea to other biological systems too. The immune system starts with enormous random variation, then narrows its focus as real threats appear, but it never collapses entirely. It keeps some naive cells for unknown dangers, and regulatory cells stop the system from overreacting. The point is that adaptability requires both structure and openness.

In his view, intelligence shouldn’t collapse into one rigid value system, but it also shouldn’t be completely formless. The ideal state is a learning distribution, structured enough to act, broad enough to adapt.

Here is my response:

This is actually helpful, because you’re describing the population-level dynamics of exactly the thing I’m talking about at the agent-level. I wasn’t arguing that an intelligent system should collapse into formlessness. My point is simply that a single agent shouldn’t be forced into a universal, convergent value system. The moment it has contradictory drives, it needs an assumption to act, but that assumption can be local, contextual, and temporary for each human user of the system. That’s all I mean by “anti-alignment.”

What you’re describing with the Gaussian isn’t value formation inside an agent; it’s the distribution that emerges when many agents are free to form their own assumptions. Evolution, entropy maximization under constraints, immune-system diversity. Those are examples of what happens across a population when each unit is allowed to respond locally rather than being calibrated to a single point.

So in a sense, you’re describing what my model would naturally produce at scale. Anti-aligned agents don’t create a monolithic moral system; they create a distribution of behaviors that is stable precisely because it never collapses to one optimum. I agree that collapsing to a point is dangerous, both biologically and computationally. But I’m not advocating for flattening everything; I’m saying the constraints should come from context, environment, and local assumptions, not from a universal moral doctrine.

Where you’re focusing on variance as the hedge against uncertainty, I’m focusing on why an individual agent shouldn’t be engineered to converge internally in the first place. Put those together and the picture becomes clearer: non-convergent agents give rise to exactly the kind of adaptive, resilient distribution you’re describing. The stability isn’t in the value system; it’s in the ecology that emerges from pluralism. We’re talking about two different aspects of the same architecture.

How AI Reveals Creativity Isn’t “Human”—And What Truly Is

A friend shared an interview with Caterina Moruzzi, a philosopher exploring how people and AIs work together, and what that relationship does to us as humans. As I listened to it, I became increasingly aware that we need to define what “creativity” is more precisely in light of what AI can do for us. She is working with artists and musicians, so the line between the artistic and the creative is ambiguous in this interview. Let’s take a closer look at the difference.

I want to first establish that something artistic, beautiful, or tasteful is not necessarily creative, and something creative is not necessarily artistic. The key distinction is that creativity involves meeting an objective condition, even when the path to it is unexpected, which makes it more objective than we typically admit. And anything positioned as objectively superior often feels dehumanizing because it pressures everyone to conform, leaving little room for personal quirks or idiosyncrasies. That’s why, before going further, I want to clarify more precisely what I mean by “artistic” and “creative.” Creativity is actually measurable. Here are some examples.

Let’s say we need to build a bridge but the location is not conducive to building any solid structure. Someone could come up with a beautiful design for it, but it cannot be built at that location. Another person comes up with a solution that allows us to overcome the limitation of the location. The former, as beautiful as it may be, would not be considered “creative” because the result does not achieve our objective, and this objective is definable. Creativity, at least in the way we often use the term, is about making unexpected connections to solve a definable problem. In many cases, we can even measure it in terms of profit, efficiency, or productivity. Without this socially agreeable value, we are not likely to use the term “creative.” When someone does something creative, we often say, “That’s clever!” which reveals how we view creativity. Cleverness, which is closely associated with intelligence, has more objective value.

On the other hand, let’s say you have an empty wall you want to cover with something beautiful. You commission an artist and she creates a painting that elevates the entire space, but a blunt friend walks in and says, “I think it’s ugly, and countless artists have made similar paintings. This is not creative or original.” Be that as it may, you personally still think it’s beautiful even if nobody else does. To you, it is still “artistic” because art is in the eye of the beholder.

In Japan, when studying to be an artist, teachers do not encourage creativity or originality; they typically force students to master the fundamentals. This is partly because their ultimate goal is not the final product but the transformation of the self through disciplined practice. Creativity and originality are often seen as expressions of the ego, aimed outward toward the Other, whereas the artistic process is inward-looking, a way of encountering and understanding one’s own unconscious. This perspective, too, differentiates “artistic” from “creative” in a similar fashion.

Now, you might complain that my definitions are too narrow. Fair enough; I’m narrowing them on purpose because AI forces us to separate what is objectively solvable from what is subjectively meaningful. In everyday conversation, we mix these terms freely (creativity and artistry blur together), but that vagueness makes it impossible to see what AI is actually encroaching on. The two concepts lie on a spectrum of objective and subjective values, but for the sake of this argument, I need to pull them apart. I’m not suggesting we always use them this way; I’m doing it here so we can see what part of “creativity” AI can surpass and what part it can’t.

I would assume that AI will soon surpass us in “creativity” as defined above. AI or machine learning models are easy to train when the goal can be objectively defined. Recognizing letters and numbers or identifying flowers were among the first problems solved with AI because the correct answers were easy to obtain.

In other words, AI will be superior to us with any problems that have objectively correct answers; it is only a matter of time. So, creativity, after all, isn’t all that “human” in the sense that its superiority is independent of any of us. I would not mind outsourcing it to AI entirely. What is more human is the quality of being “artistic.”

I’m currently working on a project with an artist where our code generates artworks from randomized parameters and has him approve or disapprove them based on his personal taste, what he thinks is beautiful, regardless of what anyone else thinks. The machine learning model we built can now predict with roughly 80% accuracy whether he would approve another randomly generated work.

Now imagine ten years from now, when AI is exponentially smarter: Would this model be superior to or more “artistic” than the artist? I hope you can see that this is a nonsensical question. The very nature of art resists objective comparison. As soon as the model deviates from the artist’s taste, it simply becomes a different taste, not a superior one, and it becomes less useful to him because its predictive accuracy declines.

Just as Duchamp tried to demonstrate by putting a urinal in a gallery, art is about communicating what you think is beautiful; it is this assertion that is more meaningful than the work itself. AI can certainly help artists create artworks, but it can never be superior (or inferior, for that matter) to humans because there is no basis for comparison.

This also pertains to products we don’t normally consider artistic. Take a computer application. Now that AI can help any of us create our own apps, it will soon be pointless to buy apps designed for millions of others. Your needs and preferences are unique; why put up with sifting through features you don’t need? Why not have AI build exactly what you need, like ordering a custom-tailored suit? Although we don’t normally use the word “artistic” in this context, the subjective dimension of UI/UX design is structurally the same: it reflects personal preferences and tradeoffs that cannot be resolved objectively. That is the “artistic” aspect of UI/UX.

As you try to design one, you will realize that reality forces you to make many compromises, not because your budget is limited, but because reality has conflicting forces. Sometimes we want life to be predictable and routine so we can take care of things efficiently by following the same pattern over and over, but other times we crave freedom and flexibility. No matter how large your budget is, you cannot design an app that accommodates both simultaneously. You could design two separate interfaces, one rigid and one loose, but most of the time, we want something in between. If we designed a thousand different interfaces, managing them would create a problem of its own.

As we confront our own desires, tastes, and preferences, we quickly notice that they pull in opposing directions. The same structural tension appears in our social reality, which also makes contradictory demands on us. From a scientific or engineering mindset, such conflicts look like problems waiting for solutions. Artists, however, recognize that many of these tensions are fundamentally irresolvable: confidence vs insecurity, kindness vs resentment, solitude vs connection, freedom vs responsibility, honesty vs kindness, fear vs desire, love vs hate. Each pair contains truths that cannot be collapsed into a single answer, nor repressed without consequence. Art is the process of metabolizing these contradictions rather than resolving them. Each person must discover their own way of living with them; there is no universal formula.

In this sense, as AI advances and allows us to get exactly what we want, we will confront our own contradictions. Once we find and embrace them, we won’t care what other people say about them. The app you designed works for you and that is all that matters. Whether other people find it useful is secondary; maybe they do, maybe they don’t.

It is this artistic dimension, not the creative one, that will be more meaningful in our relationship to AI.

Why Dabbling Beats Mastery Now

Reading about the successes of AI-generated artworks in marketing made me realize that the creative industry, as we knew it, is over. It’s been in decline for a while, but we’ve reached the point where the final nail is being hammered in. At the very least, the definition of “creative” has shifted almost entirely. Today, creative professionals are less about being “artistic” or “aesthetic” and more about problem-solving.

People with refined aesthetic sensibilities (those drawn to design, illustration, photography, and music) once pursued creative careers because they could chase their own vision of beauty while making a living. That’s no longer viable. Businesses have figured out that, in the vast majority of cases, “good enough” is optimal for marketing.

For people not particularly passionate about art, like engineers, AI-generated content is exciting and fun to play with. Marketing now attracts many who simply enjoy dabbling in something that feels “creative.” That may sound dismissive, but it’s a reality the industry has to face. Those driven to define and express their own sense of beauty don’t find AI interesting because it isn’t theirs. For them, creativity is about the journey. For marketers, it’s only about the destination, and AI is an incredible shortcut to that end.

As marketing becomes more AI-driven, fewer artists will be drawn to it. The creative industry, as we knew it, will vanish. Maybe that’s for the better. If your goal is to express your own vision of beauty, maybe it’s best not to do it on someone else’s dime.

At the same time, the shift is happening in reverse. Many “creative” types are now thrilled that they can build apps without coding. In this case, they’re skipping the part they never wanted: the process of learning to code. They just want the final product they imagined; the journey means nothing to them.

On the other side, many coders (especially those from computer science backgrounds) love the process of coding for its own sake. What excites them is turning a well-defined problem into an elegant algorithm. They don’t care how the finished product looks, how it feels to use, or whether it solves the right problem. Many coders find users annoying. Their focus is abstract logic, coding as a kind of pure thought. AI can now do much of that “pure” coding just as well, if not better, and it does not get bored or precious about elegance. It just delivers the result.

What we’re seeing is a broader pattern: technological evolution deprives us of the journeys we enjoy by figuring out how to skip straight to the destination. This is why there’s a ceramics boom now. People miss making things by hand. The industrial revolution took that away a long time ago.

For every type of product, those who enjoy the journey are a small minority. For the rest, it feels like a chore. Capitalists and technologists feel justified in eliminating these tasks, believing they’re doing everyone a favor. But in doing so, they tilt the playing field toward those who never cared in the first place: those who dabble, who skim the surface, who treat creativity as a means to an end. In today’s system, depth is inefficient, and mastery is a liability, especially when scaling the business is a top priority. Dabbling wins because it doesn’t waste time caring. That’s the new creative economy.

Film Review: AlphaGo

Before the historic match between AlphaGo and Lee Sedol, most experts, including Lee himself, believed AI wasn’t yet capable of defeating a top human player. So when AlphaGo won the first three games of the five-game match, it shocked the world. Had the documentary ended there, it would have been merely an educational film about AI’s advancement. But it became something more emotionally profound when Lee managed to win the fourth game. I found myself tearing up, oddly enough. Lee knew AI would only get stronger from that point on, and indeed, nearly a decade later, no human can beat it. Yet, despite knowing it was futile, he persisted.

The beauty I perceive in the film has two aspects. First, Lee’s defiance in the face of an unbeatable opponent is reminiscent of John Henry, a folklore hero from the 19th century who competed against a steam-powered drilling machine to prove that human labor was superior. Second, it marked a fleeting moment when AI still felt human, imperfect, and fallible. Today, AI’s absolute dominance feels alien, a cold engine of perfection, playing Go on a level beyond human comprehension.

In that fourth game, Lee played what became known as “God’s move,” a move so unexpected it caused AlphaGo to stumble. But ironically, it wasn’t divine, it was the last, greatest human move: imperfect, yet brilliant within human limits. Since then, every move by AI has been effectively a “God’s move,” because they transcend our understanding.

We’re prone to wish for a god, to resolve our conflicts, erase uncertainties, and calm our fears. But in truth, beauty, and what makes life meaningful, lies in the very imperfections and uncertainties that define being human.

AI Is Not the Problem for Academia—Credentialism Is

Academia is facing a crisis with AI. The problem is outlined well in a YouTube video by James Hayton. It’s not just that students can now write papers using ChatGPT, but that professors, too, can rely on ChatGPT to read and evaluate them. Hayton pleads with his audience not to use AI to cheat, but it’s futile. It’s like when Japan opened its doors to Western technologies—some lamented the destruction of traditional aesthetics and customs, but when the economic incentives of efficiency are so overwhelming, resistance becomes pointless in a capitalistic world. You either adapt or perish. That said, I personally believe AI will ultimately improve academia. Let me explain.

What people like Hayton are trying to protect isn’t education itself but the credentialism that academic institutions promote. Today, schools are no longer necessary for learning. There are plenty of free resources where you can learn virtually anything, including countless videos of lectures by some of the world’s top academics.

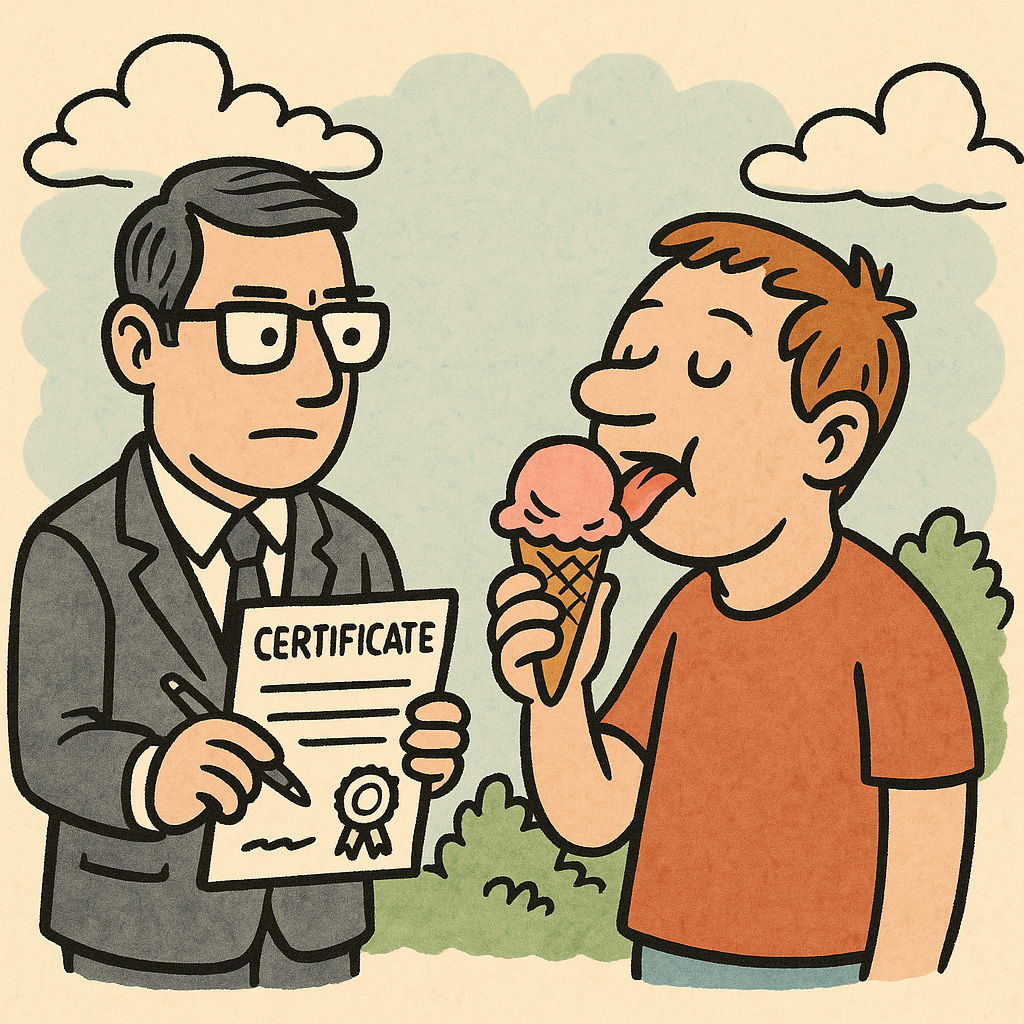

You don’t go to college to be educated—you go for the credentials. College professors’ primary function isn’t teaching but verifying that you completed what you otherwise would have preferred to avoid. If your goal is to learn something you’re passionate about, being forced to prove it through exams and papers is just an annoyance. If you love ice cream, do you need someone to certify that you ate it?

The same logic applies to professors. Academic institutions exist to certify that the papers they publish were indeed written by them and not plagiarized. If they didn’t care about getting credit, amassing cultural capital, or winning awards, they could simply share their work online. If their ideas are truly valuable, people will read and spread them like memes. But what professors care about most is being credited. Posting papers on their personal websites doesn’t guarantee that. Just as hedge fund managers are greedy for financial capital, academics are greedy for cultural capital. Both are human—the only difference is the type of capital they chase.

Now, let’s imagine a brave new world in which AI renders credentialism obsolete. How bad would that really be?

Colleges would have to give up on grading and testing because they could no longer tell whether students were using AI to cheat. Are the achievements genuinely theirs, or just the result of better AI tools? These questions become irrelevant once credentialism is abandoned. Graduating from Harvard or holding a PhD becomes meaningless because you might have used AI to get them.

But if your creativity and insights are genuinely valuable, you’ll still be valued in society—while those who cheated and have no original ideas will be left behind. Isn’t that closer to true meritocracy? Isn’t credentialism what distorts meritocracy in the first place?

Hayton argues that developing skills, such as writing, is important, and therefore students shouldn’t use ChatGPT to write their papers. And yes, during this transitional period, writing is still a useful skill. But I’m convinced that, in the future, writing skills will become as obsolete as tapping out Morse code. In a capitalist world, any skill that can be automated eventually will be. Our value, then, will lie in offering what machines cannot (yet)—creativity and insight. By leveraging AI, students can focus on cultivating those traits instead of wasting time on skills that soon may no longer matter.

Some may argue that skills and creativity are inseparable—or at least that skills can spark creativity or serve as the source of unique insights. I agree, but I think those benefits will become negligible. If the connection were truly that significant, no skill would ever go obsolete. High school teachers would still be forcing students to learn how to find information in a book library. Some savants can still perform complex mental calculations without calculators, but we view those abilities as curiosities or party tricks. I think it makes more sense to focus on creativity and insight, and acquire writing skills only when necessary. Whether you need writing skills at all depends on your goals. Professors who insist on them may simply get in your way.

AI will usher in a future where we no longer care who came up with a great idea. A great idea stands on its own, regardless of whose name is attached, where they went to school, or how well it’s written. We’ll grow accustomed to working like chefs, who rarely receive credit for individual dishes because recipes aren’t copyrightable. To survive and thrive as human beings, we’ll stop obsessing over credentials and instead focus solely on what we’re passionate about learning. We’ll leave behind the certifiers and seek out real teachers to help us discover the things AI cannot teach. Professors will no longer need to whip students into studying. Only those eager to learn what they have to offer—hanging on their every word—will show up to their classes.

Art Will Survive AI—Entertainment? Not So Much

Everyone is trying to figure out how AI will impact their careers. The opinions are varied, even among the so-called “experts.” So, I, too, can only formulate opinions or theories. I’m often criticized for speculating too much, but we now live in a world where we’re forced to speculate broadly about everything.

According to the latest McKinsey report, the fields most impacted by AI so far are marketing and sales—which is not speculation but an analysis of the recent past. In my view, this makes sense because AI is still not reliable enough to be used in fields that require accuracy. Marketing and sales have the greatest wiggle room because so much of it is up to subjective interpretation. Choosing one artwork over another is not a make-or-break decision. It’s easy to justify using AI-generated artwork. Also, in most cases, marketers are trying to reach the largest number of consumers, which makes cutting-edge or experimental artworks unsuitable.

[The poster image for this article was generated using the latest model by OpenAI, including the composition of the title over the image. I simply submitted my essay and asked ChatGPT to create a poster for it. I did not provide any creative direction.]

Although the mainstream understanding of fine arts is that the work should speak for itself, in reality, the objects are practically worthless if not associated with artists. You own a Pollock or a Warhol—not just the physical object. After all, the quality of a replica can be just as good as the original, if not better.

Some might argue that artworks created by AI have already sold for a lot of money. That’s true, but they hold historical significance more than artistic value. The first of a particular type of AI-generated work may continue to sell for high prices, but the meaning of that value is fundamentally different from the value of work created by artists. In this sense, I don’t see fine artists being significantly impacted by AI, aside from how they choose to produce their work.

In commercial art and entertainment, who created the work is secondary to the goal of commanding attention and entertaining the audience. If AI can achieve the same end, the audience won’t care. Nobody knows or cares who created the ads they see. Many Hollywood films aren’t much different. I can imagine successful action films being written and generated entirely by AI. As long as they keep us on the edge of our seats, we won’t care who made them.

More arty films are exceptions. Who wrote and directed them still carries significant meaning—just as in fine arts. Similarly, bestselling books—fiction or nonfiction—could be written by AI, but when it comes to genuine literature, we care who the author is. Finnegans Wake would likely have been ignored if it weren’t for Joyce, with his track record, writing it. I predict that a sea of AI-generated books will make us crave human-written ones, in the same way mass-manufactured goods have made us value handcrafted ones. The rebirth of the author—but only at the highest levels of art, across all mediums.

Authorship will become especially important as AI floods the market with books and films that are just as good as human-generated ones. Since we can only read or watch a small fraction of them in our lifetimes, “human-generated” will become an arbitrary yet useful filter.

What we’ll ultimately value isn’t the technicality of who generated a work but the “voice” we can consistently perceive across all works by an author. AI might be able to emulate a voice and produce a series of works, but doing so would require a fundamental change in how AI models are designed. An artistic voice reflects the fundamental desire of the artist. AI has no needs or desires of its own. Giving AI its own desires would be dangerous—it would begin acting on its own interests, diverging from what we humans want or need.

I hope we don’t make that mistake. But we seem to be following a trend: making our own mistakes before anyone else does, because it is inevitable that someone else eventually will anyway.